In my previous article, I discussed the theory behind random number generation along with the sources modern computer systems tend to use to seed their randomisation algorithms.

From a practical standpoint, an important question remains: what is the most efficient way to generate random data with a sufficient measure of randomness?

In all cases, I will be using a relatively low-powered Unix system, the environment being monitored throughout to make sure that issues such as lack of RAM, disk space or CPU share do not act as limiting factors in the tests.

The four methods of random number generation I will be analysing are:

- Output from

/dev/zero./dev/zerooutputs a string of zeroes, and is included as a benchmark for execution time, as well as an example of what non-random data looks like when put through randomness tests. - Output from

/dev/random. As its name suggests,/dev/randomaims to output random data, coming from the Unix kernel’s random number generator, which gathers environmental noise from hardware like device drivers into an entropy pool. By keeping track of the number of bits of entropy in the pool (i.e. the size of the pool),/dev/randomensures that data is only returned if there is sufficient randomness in the pool that has not been previously used. If there is not enough entropy available,/dev/randomwill block (pause) until enough new randomness has been generated to continue. (Think of this like filling a bath with water — if water is streaming out of a tap slowly, and a bucket is trying to scoop out a large amount of water from the half-filled bath, then at some point the bucket will have to wait until enough water has come through the tap before it can continue.) - Output from

/dev/urandom. Like/dev/random,/dev/urandomuses the same entropy pool to generate its random data. However, if there is not enough bits of entropy left in the pool,/dev/urandomwill re-use previous bits of entropy to seed its ongoing random number generation — therefore,/dev/urandomwill not block in the same way as/dev/random. However, it is theoretically possible that a cryptographic technique exists to weaken the security of applications who have shared the use of the entropy pool using/dev/urandom(although no such technique is currently known). - Output from the OpenSSL package. OpenSSL is installed on many systems, relying on it to provide security for most SSL (https) traffic on the Internet. In order for the protocol to initialise the connection, it must have a source of randomness. It initially seeds this using data from

/dev/urandom‘s entropy pool, and thereafter reseeds itself either from its own buffer or manually using a source of entropy from the user or environment.

Test #1: how efficient are each of these methods at producing data?

For each method above, the time taken for the system to produce 100MB of data was measured. Two output locations were measured for each method — to /dev/null and to disk — to ensure that the disk write speed (or volatility of the write rate) did not have any impact on the time taken for the overall process to complete.

| Method | Command | Execution time |

|---|---|---|

| /dev/zero | time head -c 100000000 /dev/zero > /dev/null | 0.03 seconds |

time head -c 100000000 /dev/zero > rand-zeros | 0.30 seconds | |

| /dev/random | time head -c 100000000 /dev/random > /dev/null | 2 minutes 8 seconds |

time head -c 100000000 /dev/random > rand-random | 2 minutes 9 seconds | |

| /dev/urandom | time head -c 100000000 /dev/urandom > /dev/null | 20.4 seconds |

time head -c 100000000 /dev/urandom > rand-random | 21.2 seconds | |

| OpenSSL | time openssl rand -out /dev/null 100000000 | 7.1 seconds |

time openssl rand -out rand-openssl 100000000 | 7.3 seconds |

Observations:

/dev/zerowas extremely quick to complete, which suggests that the increased amount of time from all other methods is due to the computational complexity of producing random data.- Of the proper candidates, the OpenSSL library performed the best — generating 100MB file of random binary data in 7.1 seconds. Another candidate,

/dev/urandom, was able to produce the same amount of data in 20.4 seconds (approximately three times slower). /dev/randomtook much longer than all other methods due to the previously-mentioned property of blocking on an empty entropy pool.

Test #2: how random is the data?

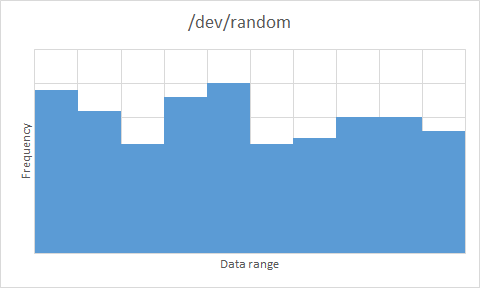

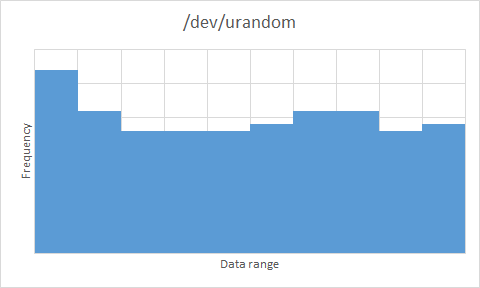

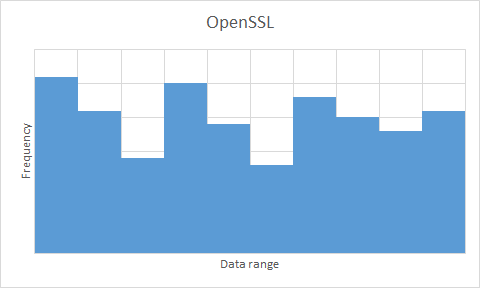

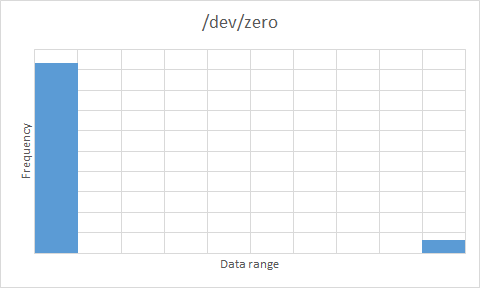

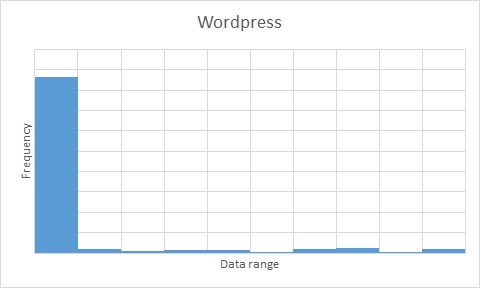

An efficient random data generation algorithm is worthless if the data it produces is not sufficiently random. For this test, I am making use of the Diehard test suite, which produces 200 p-values as an output of its battery of tests for randomisation. A sufficiently random data set will output p-values according to a uniform distribution over the interval \(\left [ 0,1 \right )\). The results are pictured below as histograms to present the data in a visual way — you can also download the raw Diehard output for a more detailed view.

| Source | Test results |

|---|---|

/dev/random |  |

/dev/urandom |  |

OpenSSL |  |

/dev/zero |  |

Observations:

- As expected,

/dev/zerocompletely failed the randomisation test. - All of

/dev/random,/dev/urandomand OpenSSL produce sufficient randomness. Some of them look less than uniform – OpenSSL in particular – but bear in mind that there are only 200 data points to work with. As a comparison, I performed the same test with the latest WordPress .tar.gz archive (v3.5.1 at the time of writing) – this has been put through a data compression algorithm, so we would expect a high level of entropy (otherwise the compression algorithm isn’t doing a great job). The results weren’t encouraging (see below) – with results so similar to/dev/zerofor an intuitively high-entropy archive, the three serious contenders are very much a step above in terms of data randomness, meaning that the apparent bias in the uniform distributions is not a major factor in our result.

Conclusion

/dev/random,/dev/urandomand OpenSSL are all sufficiently good sources of random data on a Unix system, as evidenced by the Diehard battery of randomness tests.- In terms of performance,

/dev/randomhas the potential to block if the entropy pool is depleted. However, as seen from the randomness tests, there is no compelling reason to use/dev/randomover/dev/urandomor OpenSSL. - OpenSSL generates random data approximately three times faster than its closest rival,

/dev/urandom. Although it is a fairly standard Unix package, it is not guaranteed to exist on all Unix systems (in particular, systems that do not act as web servers).

TL;DR: OpenSSL is the most efficient tested source of random data on a Unix system. Where the OpenSSL package is not available, /dev/urandom is a practical alternative.